Pathogenèse sous-jacente aux manifestations neurologiques du syndrome Long COVID et thérapeutiques potentielles

par

Albert Leng 1,

Manuj Shah 1,

Syed Ameen Ahmad 2,

Lavienraj Premraj 3,4,

Karin Wildi 4,

Gianluigi

Li Bassi4,5,6,7,8,

Carlos A. Pardo 2,9,

Alex Choi 10 et

Sung-Min

Cho11,*

1

Département de chirurgie, École de médecine de l’Université Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD 21205, États-Unis

2

Département de neurologie, École de médecine de l’Université Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD 21205, États-Unis

3

Département de neurologie, Griffith University School of Medicine, Gold Coast, Brisbane, QLD 4215, Australie

4

Groupe de recherche en soins intensifs, Hôpital Prince Charles, Brisbane, QLD 4032, Australie

5

Faculté de médecine, Université du Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australie

6

Institut de la santé et de l’innovation biomédicale, Université de technologie du Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4000, Australie

7

Unité de soins intensifs, St Andrew’s War Memorial Hospital et Wesley Hospital, Uniting Care Hospitals, Brisbane, QLD 4000, Australie

8

Wesley Medical Research, Auchenflower, QLD 4066, Australie

9

Département de pathologie, École de médecine de l’Université Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD 21205, États-Unis

10

Division des soins intensifs en neurosciences, département de neurochirurgie, UT Houston, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Cellules 2023, 12(5), 816 ; https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12050816

Reçu : 23 janvier 2023/Révisé : 28 février 2023/Accepté : 3 mars 2023 /Publié : 6 mars 2023

(Cet article fait partie du numéro spécial Insights into Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms de NeuroCOVID)

Télécharger

Parcourir les chiffres

Rapports d’examen Versions Notes

Résumé

L’apparition de symptômes à long terme de la maladie à coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) plus de quatre semaines après l’infection primaire, appelée « longue COVID » ou séquelle post-aiguë de COVID-19 (PASC), peut impliquer des complications neurologiques persistantes chez un tiers des patients et se manifester par de la fatigue, un « brouillard cérébral », des maux de tête, des troubles cognitifs, une dysautonomie, des symptômes neuropsychiatriques, une anosmie, une hypogée et une neuropathie périphérique. Les mécanismes pathogènes de ces symptômes du COVID long restent largement obscurs ; cependant, plusieurs hypothèses impliquent des mécanismes pathogènes systémiques et du système nerveux, tels que la persistance du virus SARS-CoV2 et la neuroinvasion, une réponse immunologique anormale, l’auto-immunité, les coagulopathies et l’endothéliopathie. En dehors du SNC, le SARS-CoV-2 peut envahir les cellules de soutien et les cellules souches de l’épithélium olfactif, ce qui entraîne des altérations persistantes de la fonction olfactive. L’infection par le SRAS-CoV-2 peut induire des anomalies de l’immunité innée et adaptative, notamment une expansion des monocytes, un épuisement des lymphocytes T et une libération prolongée de cytokines, ce qui peut provoquer des réponses neuroinflammatoires et une activation de la microglie, des anomalies de la substance blanche et des modifications microvasculaires. En outre, la formation de caillots microvasculaires peut occlure les capillaires et l’endothéliopathie, due à l’activité de la protéase du SRAS-CoV-2 et à l’activation du complément, peut contribuer aux lésions neuronales hypoxiques et au dysfonctionnement de la barrière hémato-encéphalique, respectivement. Les traitements actuels ciblent les mécanismes pathologiques en utilisant des antiviraux, en diminuant l’inflammation et en favorisant la régénération de l’épithélium olfactif. Ainsi, à partir des preuves de laboratoire et des essais cliniques de la littérature, nous avons cherché à synthétiser les voies physiopathologiques qui sous-tendent les symptômes neurologiques du COVID long et les thérapeutiques potentielles.

Mots-clés :

COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; COVID long; manifestations neurologiques ; complications neurologiques; résultats; brouillard cérébral

1. Introduction

Le coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) est une maladie multisystémique causée par une infection par le coronavirus 2 du syndrome respiratoire aigu sévère (SARS-CoV-2). Les Centres de contrôle et de prévention des maladies (CDC) considèrent que le COVID-19 est long lorsque les symptômes durent plus de quatre semaines après l’infection initiale. L’ensemble des symptômes porte de nombreux noms, notamment « COVID longue », « COVID chronique », « séquelles post-aiguës de COVID-19 » et « affections post-COVID ». Des études antérieures ont fait état de différentes fréquences de COVID longue, allant de 13,3 % à 54 % des patients après l’infection initiale par le SRAS-CoV-2[1,2]. Notamment, un sous-type de COVID longue comprend des séquelles neurologiques, que certains rapports ont identifiées comme étant présentes chez un tiers des patients au cours des six premiers mois suivant l’infection aiguë par COVID-19. Ces symptômes se manifestent par des anomalies objectives à l’examen neurologique, telles que des déficits moteurs/sensoriels, une hyposmie, des déficits cognitifs et des tremblements posturaux[3].

Alors que des études antérieures ont proposé des mécanismes potentiels pour les symptômes du COVID long, il existe peu de rapports qui synthétisent et évaluent la physiopathologie des manifestations neurologiques du COVID long et ses options thérapeutiques. Ce faisant, nous établissons un lien entre la recherche en sciences fondamentales, la recherche translationnelle et les résultats des études épidémiologiques et cliniques.

2. Preuve clinique d’une atteinte neurologique dans le cas d’un COVID long

2.1. L’épidémiologie

Dans une méta-analyse portant sur 257 348 patients atteints de COVID-19, certains des symptômes les plus fréquents de COVID longue durée après trois à six mois comprenaient la fatigue (32 %), la dyspnée (25 %) et les difficultés de concentration (22 %), ce qui reflète la nature multisystémique de la COVID longue durée[4].

In addition to these symptoms, there is a specific cluster of specific neurological symptoms and sequelae of long COVID. For instance, in a sample of 10,530 long COVID patients at a 12-week follow-up, some of the most common neurological symptoms included fatigue (37%), brain fog (32%), memory issues (28%), attention disorder (22%), myalgia (28%), anosmia (12%), dysgeusia (10%), and headaches (15%) [5]. Some of these symptoms continue to persist at longer follow-up periods—including six-month and one-year follow-ups after initial diagnosis [6,7,8]. Considering these studies, it is evident that cognitive symptoms, headaches, sleep disorders, neuropathies, and autonomic dysfunction are some of the most common neurological manifestations of long COVID. Other, less frequent, neurological sequelae include dysexecutive syndrome, ataxia, and motor disturbances [9,10]. In all, these symptoms can lead to significant dysfunction and disability, with around 30% of long COVID patients aged 30–59 indicating that their neurological symptoms made them severely unable to function at work [10].

2.2. Risk Factors

Specific demographic risk factors for long COVID have been identified. Females were reported to have a higher risk of developing long COVID symptomatology [1,11,12,13,14,15]. Information on age is less unanimous. Several studies have reported that older patients (vs. younger) are at increased risk of developing long COVID [1,14,15,16,17]. However, other studies have shown that younger patients are at increased risk, while some studies have shown no association between age and the development of long COVID [11,12,16,18]. Regarding race/ethnicity, a study of 8325 patients with long COVID reported that non-Hispanic white patients were more likely to develop long COVID while non-Hispanic black patients were less likely to develop long COVID [14]. Alternatively, in a longitudinal analysis of 1038 patients, race/ethnicity had no significant association with long COVID occurrence [17].

However, there are sparse data on the specific risk factors for neurological manifestations of long COVID. In one study, female sex and older age were shown to be associated with the neurological manifestations of long COVID, while race/ethnicity, COVID-19 severity, and other comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, and congestive heart failure, were not [19]. Additionally, it has been noted that an increased severity of neurological symptoms is associated with a diminished CD4+ T cell response against the spike protein, suggesting that the T cell response is necessary to counteract the severity of neurological long COVID. In this cohort, mRNA COVID-19 vaccination elevated the T cell response and helped diminish the severity of neurological symptoms in long COVID [20].

Yet overall, the impact of demographic factors such as race/ethnicity, as well as comorbidities on long COVID, needs more dedicated epidemiological studies as many of the previous studies are influenced by geographical and recruitment biases.

Focusing on biological and medical factors influencing long COVID, studies have focused on the magnitude and severity derived from the acute phase of COVID-19. For patients who required intensive care unit (ICU) admission in the acute phase of COVID-19, long-term impairment following ICU discharge appears to be frequent. For example, in a study of 117 patients that required high-flow nasal cannulae, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, or invasive mechanical ventilation, 86% reported long COVID symptoms at a six-month follow-up. These included, but were not limited to, fatigue, muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and smell/taste disorders [6,17]. Metabolic risk factors such as a high body mass index, the presence of insulin resistance, and diabetes mellitus have been associated with long COVID [14,15,16,21,22]. Not surprisingly, patients who were “hospitalized” in the acute phase of COVID-19 were more likely to develop long COVID symptoms [15,17]. Other risk factors include Epstein–Barr virus reactivation, history of smoking, exposure to air toxicants and pollutants, and the presence of chronic comorbid conditions [13,14,20,22,23].

2.3. Outcomes

An increased risk of mortality has been observed in COVID-19 patients with post-acute sequelae (defined as at least 365 days of follow-up time for long COVID symptoms). In a large study of 13,638 patients, an increased 12-month mortality risk after recovery from the initial infection was observed as compared with patients with suspected COVID-19 and who had a negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test [24]. Additionally, long COVID patients with more severe initial infections (defined by occurrence of hospitalization) had an increased 12-month mortality risk after recovery from the initial infection and subsequent development of post-acute sequelae in comparison with patients with moderate or mild initial COVID-19 infections [24]. Furthermore, age, male sex, unvaccinated status, and baseline comorbidities were associated with higher mortality in patients with long COVID when followed over time [25]. Regarding vaccination, a systematic review of 989,174 patients across different studies demonstrated that vaccination before acute COVID-19 infection was associated with a reduced risk (RR = 0.71) of developing non-neurological symptoms of long COVID [26]. Likewise, in a survey of long COVID patients who had not yet been vaccinated, most patients had an improved average symptom score, suggesting that vaccination may play a role in mitigating the symptoms of long COVID [27].

Much of the available literature focuses on mortality outcomes related to long COVID broadly. To our knowledge, there are no studies that report mortality outcomes on the neurological symptoms of long COVID specifically.

3. Mechanisms of Neurological Long COVID and Review of Therapeutics

3.1. Viral Neuroinvasion and Persistent Viral Shedding

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is known to invade human cells through engagement with specific membrane cell receptors which include angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) transmembrane receptor and activation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) cleavage. Undoubtedly, polymorphisms that alter the ACE2 and spike protein interaction, the TMPRSS2 proteolytic cleavage site, and ACE2 expression correlate with the susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 with some ACE2 variants incurring up to a three-fold increase in the development of severe disease [28,29]. Since the severity of disease is associated with the incidence of long COVID symptoms [30], there is a possibility that ACE2 and TMPRSS2 polymorphisms could potentiate long COVID as well. To our knowledge, the only study to have investigated this relationship found no predisposition of formerly identified ACE2 and TMPRSS2 polymorphisms linked to disease severity for long COVID symptoms in patients who were previously hospitalized for COVID-19 [31].

Relating specifically to neurological symptoms of long COVID, receptors are expressed by endothelial and nervous system cells such as neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [32,33,34,35,36]. However, the possibility for viral invasion of neural tissue remains highly debated. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in cortical neurons from autopsy studies and replicative potential of SARS-CoV-2 in human brain organoids implicates the neurotropic effects of the virus in the pathogenesis of neurological symptoms to some extent [36], but the possibility and mechanism of direct viral infection of the central nervous system (CNS) still remain unclear. Current proposed pathways include transsynaptic invasion by transport along the olfactory tract [37], which is highly unlikely due to the lack of ACE2 receptors and TMPRSS2 on olfactory neurons [38,39,40], and hematogenous spread through invasion of choroid plexus cells and pericytes [41,42]. The latter has been shown to occur in human neural organoid models where ACE2 receptors are heavily expressed on the apical side of the choroid epithelium, allowing for SARS-CoV-2 invasion through the vasculature, subsequent ependymal cell death, and blood–CSF barrier (B-CSF-B) disruption [41]. Despite this potential for viral neuroinvasion through hematogenous means, there is overwhelming evidence showing a lack of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and protein in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms [43,44], globally in the brain tissue from autopsy studies [45,46], and even within the choroid plexus of individuals with severe disease [47].

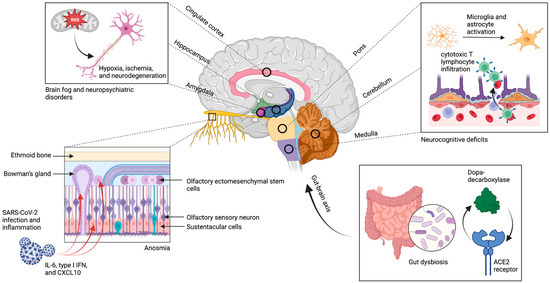

3.1.1. Invasion of Olfactory Epithelium

En revanche, l’anosmie persistante est un symptôme du COVID long qui résulte probablement des effets durables des lésions virales directes de l’épithélium olfactif. Dans le cas du COVID-19 aigu, le SARS-CoV-2 peut infecter des types de cellules non neurales qui expriment l’ACE2 dans l’épithélium olfactif, en particulier les cellules souches, les cellules périvasculaires, les cellules sustentaculaires et les cellules de la glande de Bowman(figure 1), ce qui entraîne la mort cellulaire et la perte d’uniformité démontrée chez les souris humanisées ACE2[38,48]. Contrairement à l’anosmie transitoire observée dans d’autres infections respiratoires, les études d’imagerie réalisées sur des patients atteints d’anosmie persistante due à COVID-19 ont mis en évidence des lésions importantes de l’épithélium olfactif, qui se manifestent par un amincissement des filia olfactifs et une réduction du volume des bulbes olfactifs[39,49]. En outre, des biopsies de la muqueuse olfactive de patients souffrant d’anosmie persistante d’étiologies diverses renforcent le lien entre l’amincissement de l’épithélium olfactif et la persistance des symptômes[50]. Ainsi, la perte de cellules souches et de cellules de soutien dans le neuroépithélium entraîne un échec de la réparation de l’épithélium, ce qui se traduit par un amincissement et une perte des dendrites olfactives, probablement à l’origine de l’anosmie de longue durée[51]. En outre, l’inflammation persistante mise en évidence par des niveaux élevés d’interleukine 6 (IL-6), d’interféron de type I (IFN) et de chimiokine ligand 10 à motif C-X-C (CXCL10) dans l’épithélium olfactif, secondaire à l’invasion, semble contribuer à l’anosmie de longue durée[52]. Dans l’ensemble, l’invasion des cellules de soutien par le SRAS-CoV-2 et l’inflammation locale durable qui s’ensuit causent des dommages irréversibles à l’épithélium olfactif et sont donc les principaux facteurs de l’hyposmie, de l’anosmie et de la dysgueusie persistantes.

Figure 1 :Neuroinvasion et excrétion virale persistante. Le SRAS-CoV-2 utilise le récepteur ACE2 pour envahir les cellules souches, les cellules périvasculaires, les cellules sustentaculaires et les cellules de la glande de Bowman dans l’épithélium olfactif, ce qui entraîne un amincissement chronique des filia et une perte de volume du bulbe olfactif. En outre, il existe une association entre les zones d’hypométabolisme dans le cortex, le cervelet et le tronc cérébral et la distribution spatiale des récepteurs de l’ECA2, bien qu’il y ait peu de preuves d’une neuroinvasion directe dans ces zones. L’hypothèse est plutôt que ces régions connaissent des niveaux élevés d’activation microgliale, d’infiltration de lymphocytes T cytotoxiques, de stress oxydatif, de neurodégénérescence et de démyélinisation secondaires à la neuroinvasion. Ces mécanismes persistent probablement en raison de la présence chronique de l’excrétion virale, en particulier dans le tractus gastro-intestinal où il existe une corégulation ACE2 du DDC et une implication de la voie métabolique de la dopamine. La figure a été créée avec le logiciel BioRender.

L’invasion de l’épithélium olfactif par le SARS-CoV-2 ne constitue cependant pas nécessairement une fenêtre d’opportunité pour la neuroinvasion. Bien que les premières études in vitro et in vivo puissent suggérer la possibilité d’une neuroinvasion du SNC dans la pathogenèse de la maladie dans le cas du COVID long, elles sont limitées par les preuves neuropathologiques de la présence du SRAS-CoV-2 dans le parenchyme cérébral ou le LCR des patients. En outre, les barrières anatomiques à la neuroinvasion, telles que les fibroblastes périneuraux du nerf olfactif qui enveloppent les faisceaux d’axones olfactifs et l’absence de récepteurs ACE2 pour l’entrée sur les neurones olfactifs[51], remettent encore en question la faisabilité de ce mécanisme de pathogenèse. Ainsi, à ce jour, il n’y a pas eu de démonstration validée de l’invasion et de la réplication du SRAS-CoV-2 dans le SNC.

3.1.2. Dysbiose et axe cerveau-intestin

Après une infection par le SRAS-CoV-2, il a été démontré que l’excrétion virale persistait dans les épithéliums des voies respiratoires supérieures et gastro-intestinales (GI) pendant une durée médiane de 30,9 jours et 32,5 jours, respectivement, dans les cas graves de COVID-19[53,54]. En raison de la capacité du SRAS-CoV-2 à provoquer un appauvrissement persistant des symbiotes et une dysbiose intestinale dans le tractus gastro-intestinal(55), l’excrétion virale prolongée maintient les perturbations du microbiome, ce qui entraîne probablement un dysfonctionnement de l’axe cerveau-intestin(56). Une analyse de la co-expression dans des organoïdes intestinaux humains infectés par le SRAS-CoV-2 a révélé une co-régulation par l’ACE2 de la dopa-décarboxylase (DDC) et de groupes de gènes impliqués dans la voie métabolique de la dopamine et dans l’absorption des acides aminés précurseurs des neurotransmetteurs(figure 1)[57], ce qui constitue une preuve supplémentaire de l’altération de l’axe cerveau-intestin. Ainsi, l’implication de la dysbiose intestinale et des altérations de l’axe cerveau-intestin qui persistent en raison de l’excrétion virale continue a été suggérée comme un mécanisme possible dans les manifestations neurologiques du COVID à long terme[7].

3.1.3. Reactivation of Herpesviruses

Aside from SARS-CoV-2 viral persistence, reactivation of viruses of the herpesviridae family, including Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), have also been well documented in long COVID patients. EBV and VZV, a lymphotropic gammaherpesvirus and neurotrophic alphaherpesvirus respectively, can independently affect more than 90% of people worldwide [58,59]. Both viruses can remain latent in host cells after primary infection (in memory B cells in EBV and the neurons of sensory ganglia in VZV) such that the onset of a stressor, such as another acute viral infection, can lead to the reactivation of these herpes viruses and cause inflammation and neurological symptoms. SARS-CoV-2 can act as that stressor and precipitate reactivation of other viruses in COVID-19 and long COVID symptomatology.

According to an early retrospective study of acute COVID patients post-hospitalization, 25% of patients with severe disease had increased serological titers of early antigen IgG (EA-IgG) and viral capsid antigen IgG (VCA-IgG) which serve as proxy markers for reactivation of EBV [60]. More specific to long COVID, a survey study found that two thirds of patients with symptoms 90 days after primary SARS-CoV-2 infection were positive for EBV reactivation, which was also indicated by positive titers of VCA-IgG and early antigen-diffuse IgG (EA-D IgG) [61]. Higher frequency of long COVID symptoms experienced by patients were also significantly correlated with increased EA-IgG titers. Similarly, a longitudinal study of 309 patients tracked from primary infection to convalescence revealed EBV viremia to be one of the four main risk factors for developing long COVID symptoms, with the other three being type II diabetes, SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia, and autoantibodies formation [20]. EBV reactivation has been specifically associated with memory and fatigue in long COVID. Apart from COVID-19, the immune response to EBV reactivation has been shown to reflect that of myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) which could link EBV viremia to the development of ME/CFS-like symptoms in long COVID [62,63]. This immune profile has been identified in a cross-sectional study with 215 long COVID patients where there was an elevated antibody reactivity to EBV gp23, gp42, and EA-D which all were correlated with interleukin 4 (IL-4) and IL-6 producing CD4+ T cells [64].

The same study also identified significant levels of antibody reactivity to the VZV glycoprotein E which was similarly associated with the immune profile mentioned above. VZV manifestations are also common in COVID-19, occurring in about 17.9% of patients mostly and in the form of dermatome rashes, with rare instances of encephalitis-meningitis and vasculitis [65]. Although less prominent in long COVID pathogenesis than EBV reactivation, VZV reactivation can still contribute to neurological symptoms due to its involvement with the CNS.

La persistance du SRAS-CoV-2 par le biais de l’excrétion virale incite à considérer les médicaments antiviraux comme des thérapies potentielles à long terme contre le COVID. Les médicaments antiviraux utilisés dans le traitement du COVID-19 aigu, en particulier le remdesivir, le molnupiravir, la fluvoxamine et l’association nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), ont permis de réduire considérablement la mortalité et l’hospitalisation[66,67]. Contrairement à ses homologues, le nirmatrelvir est un inhibiteur compétitif très spécifique de la protéase SARS-CoV-2-3CL et donc de la réplication virale. Le ritonavir augmente la biodisponibilité du nirmatrelvir en empêchant son métabolisme hépatique[68]. Un essai contrôlé randomisé réalisé chez des adultes non hospitalisés à haut risque atteints de COVID-19 aiguë a montré que le paxlovid réduisait rapidement la charge virale (au cinquième jour) ainsi que la mortalité et l’hospitalisation(tableau 1)[67]. Le paxlovide peut s’avérer essentiel pour réduire les symptômes neurologiques d’un COVID prolongé, secondaires à la charge virale ou à l’excrétion, tels que les troubles cognitifs persistants et l’insomnie. Dans une étude récente (preprint), Xie et al. ont comparé des patients n’ayant reçu aucun traitement antiviral ou anticorps au cours d’une infection aiguë par le virus COVID-19 (N = 47 123) à des patients traités par nirmatrelvir oral dans les cinq jours suivant un test COVID-19 positif (N = 9217). Par rapport aux témoins, les patients traités de manière aiguë par le nirmatrelvir présentaient un risque nettement plus faible de développer de longs symptômes de COVID[69]. Leur définition de la symptomatologie COVID longue comprenait 12 résultats, dont la myalgie et la déficience neurocognitive[69]. Bien que les indications exactes de son utilisation chez les patients souffrant de COVID à long terme doivent encore être définies par des protocoles d’essais cliniques randomisés(tableau 2, NCT05576662), le Paxlovid est prometteur. Nous pensons que Paxlovid peut être utile pour réduire l’excrétion virale persistante à partir de l’épithélium infecté, et peut donc réduire les mécanismes secondaires à l’invasion du SRAS-CoV-2 tels que la dysbiose intestinale et l’inflammation de la muqueuse olfactive mentionnées précédemment.

Tableau 1 :Essais publiés sur les interventions relatives aux symptômes neurologiques du COVID long.

Tableau 2 :Essais en cours sur les interventions concernant les symptômes neurologiques du COVID long.

L’utilisation d’antiviraux pour résoudre le problème de la réactivation virale dans les cas de COVID de longue durée, y compris les traitements contre les herpèsvirus tels que l’acyclovir et le valacyclovir, a été documentée, mais leur efficacité pour soulager les symptômes neurologiques des cas de COVID de longue durée n’a pas encore été évaluée[65]. Une étude rétrospective menée à Wuhan a évalué les résultats en termes de mortalité à 28 jours chez 88 patients atteints de COVID-19 et présentant une réactivation de l’EBV, traités par ganciclovir, par rapport à des témoins appariés[60]. Les patients traités au ganciclovir avaient un taux de survie significativement plus élevé que les témoins, mais les symptômes neurologiques spécifiques n’ont pas été évalués. D’autres études sont nécessaires pour démontrer l’efficacité des antiviraux spécifiques à la réactivation des herpèsvirus chez les patients atteints de COVID de longue durée.

Outre l’utilisation spécifique d’antiviraux, d’autres agents, tels que le cannabidiol, peuvent avoir une certaine efficacité antivirale en tant que thérapie pour le COVID long. On sait que le métabolite actif du cannabidiol, le 7-OH-CBD, peut bloquer la réplication du SRAS-CoV-2 en inhibant l’expression des gènes viraux, en augmentant l’expression de l’interféron et en favorisant les voies de signalisation antivirales[76]. Il a notamment été signalé que le cannabidiol régulait à la baisse l’ACE2 et le TMPRSS2[77] – des enzymes clés impliquées dans le processus d’invasion du virus SRAS-CoV-2 et dans l’évolution potentielle vers le COVID long. Un essai clinique de phase 2 (NCT04997395) a commencé à étudier la faisabilité de l’utilisation du cannabidiol comme traitement du COVID long(tableau 2). En outre, il a été démontré que le cannabidiol induit des effets neuroprotecteurs[78,79]. Dans l’ensemble, cela suggère que le cannabidiol peut aider à améliorer les symptômes neurologiques du COVID long, bien que de futurs essais cliniques soient nécessaires pour fournir des preuves supplémentaires.

3.1.5. Thérapies COVID longues apparentées : Anosmie

La régénération de la muqueuse olfactive s’est produite avec l’administration d’insuline intranasale chez les patients non-COVID-19. L’insuline, par son action en tant qu’inhibiteur de l’enzyme phosphodiestérase, peut augmenter les niveaux d’adénylate monophosphate cyclique (AMPc) et de guanylate monophosphate cyclique (GMPc) en interagissant avec le cycle de l’oxyde nitrique[80]. Ces facteurs de croissance sont connus pour stimuler l’épithélium olfactif et promouvoir la régénération[80]. Dans leur essai contrôlé randomisé (ECR) pragmatique sur une petite population (N = 38), Rezaian et al. ont évalué l’efficacité d’un traitement intranasal bihebdomadaire à base de gel mousse d’insuline protaminique (par rapport à un placebo à base de solution saline normale) sur des patients souffrant d’une hyposmie post-infectieuse légère à sévère(tableau 1)[74]. Ils ont déterminé que l’olfaction (via le score du Connecticut Chemosensory Clinical Research Centre) à quatre semaines était nettement meilleure dans les groupes traités à l’insuline (5,0 ± 0,7) par rapport au groupe placebo (3,8 ± 1,1, p < 0,05)[74]. Un essai de plus grande envergure est en cours chez les patients du groupe COVID-19(tableau 2, NCT05104424). Des interventions plus novatrices se sont également révélées prometteuses. En effet, 40 patients souffrant d’anosmie après une infection par le COVID-19 ont été randomisés entre un film intranasal d’insuline et une solution saline normale (placebo). 30 minutes après l’administration, les patients du groupe traité avaient une détection d’odeurs significativement plus importante par rapport à leur niveau de base et au groupe placebo[73]. Bien que des ECR avec des échantillons plus importants et un suivi plus long soient nécessaires, ces résultats sont prometteurs pour le traitement de l’anosmie persistante chez les personnes atteintes de COVID de longue durée.

Due to the damaging effects of local inflammation on the olfactory epithelium, corticosteroids have been used in certain patients to hasten the recovery and repopulation of the olfactory epithelium [71,81]. In 2021, an RCT of mometasone nasal spray, which included one hundred COVID-19 patients with post-infection anosmia, assigned patients to two treatment branches: mometasone furoate nasal spray with olfactory training for three weeks (N = 50) or the control group with only olfactory training (N = 50). There was no significant difference in duration of smell loss, from anosmia onset to self-reported complete recovery, between groups (p = 0.31). However, a significant improvement in smell score was recorded in both groups by week three [71]. Despite this, Singh et al. were able to demonstrate significant improvements in smell (on day five) compared with baseline (day one) using fluticasone nasal spray compared with no intervention (Table 1) [70].

It should be noted that many agents for the treatment of postinfectious hyposmia have been studied previously for non-COVID-19 patients including pentoxifylline, caffeine, theophylline, statins, minocycline, zinc, intranasal vitamin A, omega-3, and melatonin. An in-depth evaluation of their use in non-COVID-19 anosmia is outside the scope of this review. However, in their detailed systematic review, Khani et al. posit that different combinations of the above agents may be of use in long COVID depending on the etiology (viral invasion vs. inflammatory damage) [81].

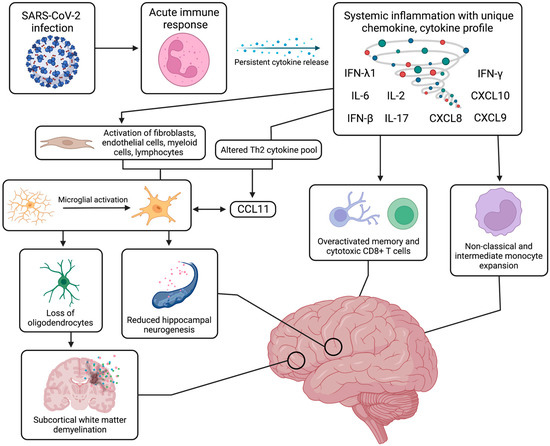

3.2. Abnormal Systemic and Neurologic Immunological Response

With a unique range of immune cell phenotypes, chemokine and cytokine production, and inflammatory molecules, the immunological response to SARS-CoV-2 infection has been widely investigated to rationalize some of the neurological symptoms of long COVID. Although autoantibody generation has been proposed, this inflammatory response has been better characterized with persistent systemic inflammation leading to expansion of monocyte subsets and T cell dysregulation, which in turn is associated with BBB dysfunction, neural glial cell reactivity, and subcortical white matter demyelination (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Systemic and neurological immune response. The systemic immune and inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 infection can continue for months after the acute recovery phase, inducing a state of persistent systemic inflammation with upregulated cytokines, such as IFN-β, IFN-λ1, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, CXCL8, CXCL9, and CXCL10. This prolonged cytokine release has been linked to activation of specific immune cell populations, such as non-classical and intermediate monocytes, as well as other cell types, such as fibroblasts and myeloid cells. From an aberrant Th2 cytokine pool, production of CCL11 is induced and leads to neuroinflammation with activation of resting microglia, which can further release increased levels of CCL11. This microglial reactivity can in turn cause reduced hippocampal neurogenesis, loss of myelinating oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursors, and ensuing subcortical white matter demyelination. These systemic and neurological mechanisms have been strongly associated with a range of cognitive impairments and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Figure was created with the BioRender software.

3.2.1. Systemic Inflammation

After SARS-CoV-2 infection, a variety of systemic inflammatory processes are upregulated, and specific immune cell populations are expanded; this disturbance of the peripheral immune system can persist for many months after the infection, which can lead to neurological symptoms. Broadly speaking, when compared with healthy controls, recovered COVID-19 individuals exhibited differences in the populations of innate immune cells, such as natural killer cells, mast cells, and C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 3+ (CXCR3+) macrophages, as well as adaptive immune cells, such as T-helper cells and regulatory T cells ([82], p. 2). With non-naive phenotypes, these cells tend to secrete and be activated by increased levels of cytokines and inflammatory markers, including, but not limited, to interferon β (IFN-β), interferon λ1 (IFN-λ1), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9), CXCL10, interleukin 2 (IL-2), IL-6, and interleukin 17 (IL-17) [83,84]. Several studies have drawn a striking similarity between the symptomatology of long COVID and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), wherein aberrant mast cell activation promotes excessive release of inflammatory mediators, such as type 1 IFNs, and cytokine activation of microglia [85,86]. Triggered by viral entry, these mast cells are commonly found at tissue–environment interfaces and may contribute to persistent systemic inflammation microvascular dysfunction with CNS disturbances in long COVID [85,86]. SARS-CoV-2 specific T cell responses have also been described to have increased breadth and magnitude. These signature T cell responses against SARS-CoV-2 increase with higher viral loads, indicated by significantly elevated levels of nucleocapsid-specific interferon gamma (IFN-γ) producing CD8+ cells in serum samples of patients with persistent SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity [87,88].

Furthermore, a study using flow cytometry on the peripheral blood of long COVID patients detected elevated expansion of non-classical monocytes (CD14dimCD16+) and intermediate monocytes (CD14+CD16+) up to 15 months post infection when compared with healthy controls [89]. Physiologically, non-classical monocytes are involved in complement-mediated and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis against viral insults and are commonly found along the luminal side of vascular endothelium, thereby contributing to BBB integrity. For example, severe long COVID patients were found to have increased levels of macrophage scavenger receptor 1 (MSR1), signifying a high degree of peripheral macrophage activation that can in turn disrupt the BBB and cause tissue damage [90]. Alternatively, intermediate monocytes specialize in antigen presentation and simultaneous secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Although this marked systemic hyperinflammatory state has not been shown to directly cause neuropsychiatric manifestations, it may contribute to disease progression via chronic activation of specific monocyte and T cell populations and neurovascular dysfunction of the BBB. These mechanisms can result in the spread of inflammatory molecules and immune cells from the periphery into the CNS, inducing a persistent neuroinflammatory response.

3.2.2. Monocyte Expansion and T Cell Dysfunction

With several parallels to the described systemic inflammation, the CNS exhibits persisting trends of monocyte expansion and T cell exhaustion after SARS-CoV-2 infection, the latter of which refers to T cells adopting a distinct cytokine profile with poor effector function. Similar to systemic trends, monocyte expansion in the CNS refers to an increase in the population of non-classical monocytes (CD14dimCD16+) and intermediate monocytes (CD14+CD16+) in CSF of long COVID patients [91,92]. Indeed, monocyte pools analyzed in long COVID patients exhibit a reduction of classical monocytes, indicated by lower levels of pan-monocytic markers and CNS border-associated macrophage phenotypes [91]. While the function of monocytes may be less understood in a chronic disease setting, the expansion of monocyte subsets with antiviral and antigen-presenting phenotypes may be implicated in long COVID symptoms due to its role in BBB disruption and neuroinflammation.

As a result of chronic stimulation by antigens, T cells can assume a distinct cytokine profile with increased inhibitory transcription factor expression and decreased effector function, a process termed exhaustion. More common in CD8+ T cells, this signature process implicates phenotypic and functional defects that can limit T cell functional responsiveness in clearing infection in chronic settings [93]. Persisting for months post infection to prevent recurring illness, CD8+ memory T cells in serum samples of long COVID patients were found to increase in number with higher levels of cytolytic granule expression but with limited breadth and reduced antigen-specific activation [94]. Although the secretion of cytolytic granzymes, IL-6, and nucleocapsid-specific IFN-γ increase in long COVID, these T cells present with limited polyfunctionality and decreased diversity of effector expression; this altered profile was strongly associated with symptoms of depression and decreased executive function [94]. Regarding localization, this population of T cells producing higher granzyme levels can be seen in certain anatomic niches, such as in microglial nodules which are hotspots for immune response activation [95]. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells also congregate near vasculature and produce a surge of cytokines that disrupts the BBB, causing vascular leakage and the propagation of inflammation [95,96]. Evidence against T cell expansion and exhaustion also exists, as one immunophenotyping study shows that persistent T cell changes and neurological deficits are associated with age rather than ongoing illness and fatigue [92].

In summary, though there is a degree of heterogeneity in respect to inflammatory molecules and immune cell populations, long COVID patients with neurological symptoms exhibit persistent systemic inflammation with pronounced differences in circulating myeloid and lymphocyte populations, including prominent peripheral B cell activation with a greater humoral response against SARS-CoV-2 [64]. Elevated levels of non-classical monocytes and intermediate monocytes can bring about altered vascular homeostasis and chronic inflammatory processes, which are largely mediated by Th1 cytokines. Increased amounts of exhausted CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with decreased central memory CD4+ T cells implicate a distinct immunological signature with decreased effector function and resulting aberrant immune engagement [64].

3.2.3. Autoantibody Generation

Autoantibody generation has been hypothesized to contribute to the persisting abnormal immunological response observed post infection. Rather than being caused by the virus directly, the autoimmune antibody reaction is suggested to be a product of the pronounced immune and inflammatory reaction [22,97]. The serologically detected autoantibodies can be categorized into antibodies against extracellular, cell surface and membrane, or intracellular targets, which include immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies against cytokines [98], angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (anti-ACE2) [99], and nuclear proteins (ANA), respectively [100].

Following activation of B cells in the periphery and cytokine abnormalities, these serologic IgG and IgA antibodies exhibit a polyclonal distribution, affect cytokine function and endothelial integrity, and can enter the CNS given the BBB disruption [90]. Although there are limited reports, these autoimmune responses have been proposed to be present with acute-onset encephalitis, seizures, meningitis, polyradiculitis, myelopathy, and neuropsychiatric symptoms [101,102,103,104,105]. Persistent ANA autoreactivity has been linked with long-term symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, and brain fog seen in long COVID [106]. Anti-ACE2 antibodies, which are associated with fatigue and myelitis, can elicit an abnormal renin–angiotensin response, cause malignant hypertension-related ischemia and upregulate thrombo-inflammatory pathways [97]. While these antibodies have been associated with neurological manifestations after SARS-CoV-2 infection, they have also been limited to parainfection and acute post-infection time periods. Furthermore, small studies have reported the lack of autoantibodies in acute COVID-19 patients presenting with encephalitis [107]. More convincingly, a recent exploratory, cross sectional study illustrated that despite patients exhibiting an array of autoantigen reactivities, the total levels of autoantibodies were definitively not elevated in the extracellular proteome of patients with long COVID compared with convalescent controls [64].

Perhaps sparked by previous demonstrations of peripheral B cell activation, research supporting autoantibody generation in the neurological manifestations of long COVID have been mostly limited to various case reports and studies that, due to sample size and timescale constraints, have limited generalizability. Though autoantibodies can drive inflammation, neuronal dysfunction, and subsequent neurodegeneration, which are all observed in long COVID, this mechanism is not as well understood and warrants further investigations to implicate it in the pathogenesis of long COVID.

Control of inflammation post-infection may attenuate persistent cytokine release, immune cell activation, and the pronounced neural immune response, thereby alleviating neurological symptoms of long COVID. Support for this rationale derives from the studies that showed lower prevalence of long COVID in those with less robust inflammatory and immune responses to acute infection, such as vaccinated patients [69,108] and those treated with antivirals [109,110]. Here, we review several promising anti-inflammatory therapies for those with long COVID.

A currently recruiting double-blinded placebo-controlled RCT assessing the efficacy of oral lithium (10 mg daily) aims to determine if fatigue, brain fog, anxiety and cognitive outcome scores improve after three weeks of lithium therapy (NCT05618587). Despite the anti-inflammatory effects of lithium, good CNS penetrance, and efficacy in reducing inflammation in patients with acute COVID-19 [111], lithium’s efficacy and benefit–risk profile in patients with long COVID and neurological symptoms have not been proven.

RSLV-132 is a novel RNase fusion protein that digests ribonucleic acid contained in autoantibodies and immune complexes generated by the humoral immune response. Therefore, RSLV-132 has applications in both autoimmune disease and post-viral syndromes caused by autoantibody generation, such as long COVID. When compared with the placebo in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome, RSLV-132 decreased fatigue, which was assessed using Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT), Fatigue Visual Analogue Score, and Profile of Fatigue Score at week 14 [112]. The phase 2 clinical trial of RSLV-132 (NCT04944121) follows patients 10 weeks after the start of treatment and assesses fatigue using Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS), FACIT scores and long COVID symptoms via questionnaires. The precise indication for RSLV-132 requires further study, as patients with long COVID may have sub-threshold or absent autoantibody levels as previously mentioned [107].

RCTs assessing the efficacy of conventional anti-inflammatory agents, such as steroids or IV immunoglobulin, are ongoing: one upcoming trial involves the randomized treatment of patients with either IV methylprednisolone, IV immunoglobulin or IV saline (NCT05350774). Depression, anxiety, and cognitive assessment scores will be compared at the end of the three-month (minimum) follow-up period. Ongoing RCTs of anti-inflammatory agents are summarized in Table 2.

Additionally, brain fog and fatigue, which are the most prevalent neurological symptoms of long COVID [5], might arise from the prolonged neuroinflammation secondary to the innate immune activation (immune cell migration across the BBB and chemokine release) and humoral activation (autoantibody generation) described above. While current trials are investigating various agents that control the systemic inflammation discussed above, dextroamphetamine–amphetamine (NCT05597722) may be suitable for use in long COVID patients to improve brain fog, given its use in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In a similar vein, low-dose naltrexone has shown promise in improving brain fog and fatigue (self-reported via questionnaire) [72]; an upcoming placebo-controlled RCT (NCT05430152) will provide greater clarity on its efficacy. Along with other mast cell mediator blockers and stabilizers used in MCAS that target mast cell overactivation and subsequent inflammation, antihistamine treatment via a combined histamine H1/H2 receptor blockade has been associated with significant symptomatic improvement in long COVID patients according to a recent observational study [75]. However, further studies are required to determine the optimal patients for the above interventions.

3.2.5. Neural Glial Cell Reactivity

One of the most prominent hypothesized mechanisms of long COVID symptomatology involves the activation of the neuroimmune system through the interplay of neural cells and glial cells, namely astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. Astrocytes are critical for CNS homeostasis as they play roles in neuron–glial cell interaction, synaptic function, and blood–brain barrier integrity. Microglia are fundamental for processes of innate immunity within the CNS and are central to synaptic function, maintaining neural networks, and supporting homeostatic repair mechanisms upon injury to the micro-environment. However, with altered cytokine activity and brain injury, glial cells can become overactivated. Evidenced by increased levels of ezrin (EZR) in long COVID patients, these reactive astrocytes upregulate NF-κB, which can cause endothelial cell death and increase extracellular glutamate, resulting in BBB disruption and hyperexcitability-induced neurodegeneration, respectively [90,113,114,115]. Similarly, it is suspected that reactive microglia lose their plasticity-promoting function and facilitate disruption of neural circuitry with the release of microglial cytokines.

Patients with neurological symptoms of long COVID were also found to have increased levels of the C-C motif chemokine ligand 11 (CCL11), an immunoregulatory chemokine that can recruit eosinophils, cross the BBB, induce microglial migration, disrupt hippocampal neurogenesis, and cause cognitive dysfunction (e.g., brain fog) [45,116]. Decreased ramification of microglia is partially stimulated by CCL11, causing the release of microglial cytokines and the death of vulnerable neuroglial cells, such as the myelinating oligodendrocytes which assist in the tuning of neural circuitry and the provision of metabolic support to axons. Mouse models and brain tissue samples of long COVID patients have shown extensive white matter-selective microglial and astrocytic reactivity, with subsequent loss of oligodendrocytes and subcortical white matter demyelination (Figure 2). As a result, circuit integrity may be compromised, thereby leading to persisting neurological symptoms [116]. Moreover, novel brain organoid models have demonstrated marked microgliosis 72 h post infection with upregulation of IFN-stimulated genes and microglial phagocytosis leading to engulfment of nerve termini and synapse elimination [117]. This observed postsynaptic destruction may persist along with chronic microglial reactivity to further propagate neurodegeneration in long COVID. Lastly, the most severe long COVID patients exhibited increased levels of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 11b (TNFRSF11B), an osteoblast-secreted decoy receptor that has been implicated in neuroinflammatory processes and in contributing to microglia overstimulation [90]. Associated with a variety of symptoms, such as cognitive dysfunction, poor psychomotor coordination, and working memory deficits, this mechanism of neural cell reactivity is not specific to COVID-19 and is in fact, strikingly similar to cancer therapy-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) [116].

The pathogenesis and neurological manifestations of long COVID implicate disturbances of neuroglial cells with resulting glial cell reactivity that can be localized to specific brain regions, such as the olfactory bulb, brainstem, and basal ganglia [45]. With persistent cytokine abnormalities and brain injury, reactive neuroglia can influence vascular and endothelial function, compromising the integrity of the BBB, and cause neurodegeneration with marked increases in extracellular glutamate leading to toxic hyperexcitability. Reactive microglia respond to increased levels of CCL11 and release microglial cytokines that can damage neural circuitry. This overactive state of microgliosis leads to a decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis, which is linked with deficits in memory and cognitive function, as well as the death of myelinating oligodendrocytes alongside white-matter selective demyelination. In summary, the most consistent neuropathological observation in all autopsy-based studies of COVID-19 patients is the prominent astroglial and microglial over-reactivity. At present, with the exception of a few anecdotal case reports, there are no neuropathological studies of long COVID conditions. Nevertheless, the neuroglial disturbances and ensuing cytotoxicity appear to facilitate persistent inflammation and subsequent axonal dysfunction in the CNS environment, leading to attention deficits, brain fog, fatigue, and anosmia [45,95].

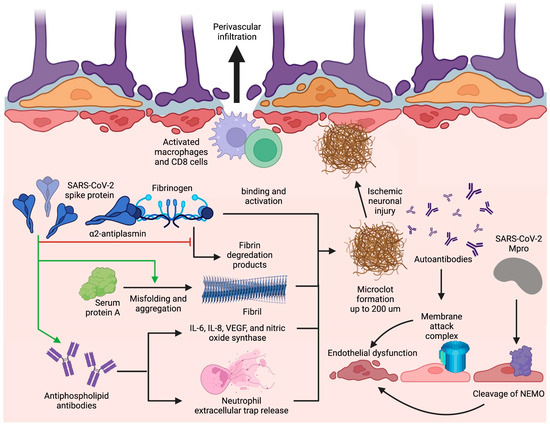

3.3. Coaguloapathies and Endotheliopathy-Associated Neurovascular Injury

COVID-19 is known to increase the risk for hemorrhages, ischemic infarcts, and hypoxic changes in the CNS during the acute phase of infection, implicating endotheliopathy and coagulopathy as important mechanisms of pathogenesis [46]. Although these neurological symptoms are not observed in high frequency among long COVID patients, small vessel thromboses (microclots) and microvascular dysfunction due to persisting mechanisms of endotheliopathy and coagulopathy could account for the neurological symptoms of long COVID that are associated with cerebrovascular disease and hypoxic-neuronal injury (Figure 3) [63].

Figure 3. Blood–brain barrier disruption and microclot formation. SARS-CoV-2 can cause increased microclot formation through spike protein interactions with fibrinogen and serum protein A that promote fibril formation and resist fibrinolysis. Antiphospholipid antibodies are also present in long COVID and can precipitate microclot formation through IL-6, IL-8, VEGF, nitric oxide synthase, and NET release. These microclots also contain α2AP which inhibit plasmin and thus prevent the degradation of fibrin, further contributing to their fibrinolysis-resistant nature. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 can induce BBB disruption through Mpro cleavage of NEMO in endothelial cells leading to cell death and string vessel formation. Figure was created with the BioRender software.

A major mechanism of thrombosis in long COVID involves a unique signature of fibrinolysis-resistant, large anomalous amyloid microclot formation present in the serum of patients with long COVID [118]. Thioflavin T staining and microscopy have determined the size of these microclots to reach upwards of 200 µm, which can adequately occlude microcapillaries, reducing cerebral blood flow and causing ischemic neuronal injury [118,119]. Microclot formation occurs due to the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with fibrinogen, which causes increased clot density, spike-enhanced release of reactive oxygen species, fibrin-induced inflammation at sites of vascular damage, and delayed fibrinolysis [119,120,121]. Additionally, interaction of the nine-residue segment SK9 located on the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein with serum amyloid A (SAA) increases fibril formation and stability, thus contributing to the amyloid nature of the microclots [122]. Proteomics pairwise analysis of digested microclot samples from long COVID patients revealed significantly elevated levels of fibrinogen alpha chains and SAA which both contribute to fibrinolysis resistance and subsequent microclot persistence (Figure 3) [118]. The same study also revealed that the inflammatory molecule α2-antiplasmin (α2AP), a potent inhibitor of plasmin, was significantly elevated in microclots from long COVID patients in comparison with patients with acute COVID; likely contributing to an aberrant fibrinolytic system in addition to anomalous microclot formation [118].

3.3.2. Antiphospholipid Antibodies

Hypercoagulability can also be precipitated by prothrombotic autoantibody formation in long COVID. Prothrombotic autoantibodies targeting phospholipids and phospholipid-binding proteins (aPLs), including anticardiolipin, anti-beta2 glycoprotein I, and anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin, were found to be present in 52% of serum samples of patients hospitalized with acute COVID-19 [123]. It is currently hypothesized that aPLs can form through molecular mimicry, neoepitope formation, or both [124]. The S1 and S2 subunits of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein could form a phospholipid-like epitope as a mechanism of molecular mimicry or, alternatively, oxidative stress due to SARS-CoV-2 may lead to the conformational change of beta2-glycoprotein I as a way of neoepitope generation. These proposed mechanisms can both result in aPL formation; however, in-vitro experimentation is needed to verify these pathologies in long COVID [124,125]. Antiphospholipid antibodies are then able to cause thrombosis through either the induction of adhesion molecule and tissue factor expression or the upregulation of IL-6, interleukin 8 (IL-8), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and nitric oxide synthase [124]. However, studies specific to these mechanisms have not yet been undertaken in the setting of long COVID. Alternatively, COVID-19-specific mechanisms of aPL-induced thrombosis include elevated platelet counts and neutrophil hyperactivity [123]. Specifically, IgG was purified from serum of COVID-19 patients with high titers of aPL and added to cultured neutrophils, increasing neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) release (Figure 3) [123]. With the persistence of the S1 subunit of the spike protein within CD16+ monocytes for up to 15 months post-infection as an epitope for aPL generation [89], aPL levels can remain elevated in long COVID.

It is still important, however, to take into account the previously mentioned insignificant autoantibody generation to the exoproteome in long COVID patients when considering the role of aPL in disease pathogenesis [64]. Thus, the interplay between anomalous microclot formation, fibrinolytic system dysfunction, and possible aPL formation likely contribute to persistent coagulopathies leading to ischemic neuronal injury in long COVID.

3.3.3. Endotheliopathy

Persistent endotheliopathy, independent of the acute COVID-19 response, has been implicated in BBB disruption and neurovascular injury. Levels of plasma markers for endotheliopathy, including von Willebrand factor (VWF) antigen, VWF propeptide, soluble thrombomodulin, and endothelial colony-forming cells, remained elevated in a cohort of patients assessed at a median of 68 days post-infection [126,127]. This prolonged endotheliopathy in long COVID can be attributed to the sustained effect by tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin 1β (IL-1β) proinflammatory cytokines [128], complement activation by immunoglobulin complexes [129], oxidative stress evidenced by elevated malondialdehyde levels [130], or by direct viral invasion of endothelial cells [113]. With regards to the immune-mediated processes, although cytokines themselves can directly activate endothelial cells, immune complexes positive for IgG and immunoglobulin M (IgM) at the vascular wall of post-mortem tissue of patients with acute COVID-19 were co-localized with membrane attack complexes (MAC) composed of activated C5b-9 complement factors [129]. The presence of MAC, paired with the previously mentioned evidence of autoantibodies to ACE2 receptors on endothelial cell surfaces [99], could very well lead to endothelial cell death. Additionally, in regards to viral invasion of endothelial cells, in vitro and in vivo experiments have elucidated the ability of SARS-CoV-2 protease Mpro to cleave NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) in endothelial cells (Figure 3), resulting in cell death, empty basement membrane tube formation (also known as string vessels), and BBB dysfunction in mice [130].

3.3.4. Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption

BBB dysfunction has been hypothesized to be at the center of the mechanisms of long-term COVID complications. BBB alterations in permeability after addition of extracted SARS-CoV-2 spike protein have been observed in microfluidic models, likely due to endotheliopathy from a pro-inflammatory response [131]. The resulting BBB permeability and microvascular injury have been indicated by perivascular leakage of fibrinogen and persistent capillary rarefaction in an autopsy and a sublingual video microscopy study of long COVID patients, respectively [129,132]. BBB dysfunction can then allow for infiltration of immune cells and cytokines from the systemic circulation that can then propagate neuroinflammation mechanisms in the CNS. Notably, the same autopsy study revealed perivascular invasion of CD68+ macrophages and CD8+ T cells (Figure 3) along with notable reactive astrogliosis which might serve a currently unidentified role in perpetuating BBB leakage [129]. This loss of BBB function is thought to be more pronounced in areas of the cerebellum and brainstem, where most pathological abnormalities have been found with prominent hypometabolism in the bilateral pons, medulla, and cerebellum of long COVID patients (Figure 1) [45,46,133]. The increased permeability at the blood and CNS interface could allow for microglial activation by systemic inflammation evidenced by the presence of microglial nodules associated with neuronophagia and neuronal loss in the hindbrain of patients with acute COVID-19 [129], likely accounting for the persisting hypometabolic pathology. Subsequent neuronal degeneration and brainstem dysfunction could explain the similarities between long COVID symptoms and ME/CFS since the association between severity of ME/CFS symptoms and brainstem dysfunction has been elucidated in previous imaging studies [134,135,136,137]. Together, all endothelial-associated mechanisms can lead to the spread of inflammatory cytokines and immune cells into the CNS, infected leukocyte extravasation across the BBB, and microhemorrhage, ultimately contributing to underlying neurological and cognitive symptoms in long COVID. Current interventions that aim to ameliorate risk of thrombotic complications are not COVID-19 specific, however, due to the implication of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in endotheliopathy, the role of nirmatrelvir or Paxlovid as Mpro inhibitors could possibly lessen BBB dysfunction. Still, a pharmacological challenge remains in demonstrating the benefit of traditional anticoagulation in patients with long COVID.

4. Conclusions

Neurological manifestations of long COVID exist as a major complication of COVID-19 post-infection, affecting up to one third of patients with COVID symptoms lasting longer than four weeks. Although SARS-CoV-2 neurotropism, viral-induced coagulopathy, endothelial disruption, systemic inflammation, cytokine overactivation and neuroglial dysfunction have been hypothesized as mechanisms associated with pathogenesis of long COVID condition, further clinical, neuropathological, and experimental models are needed to address many of the unknown questions about pathogenesis. Similarly, current and potential therapeutics to target these hypothesized pathogenic mechanisms using anti-inflammatory, anti-viral, and neuro-regenerative agents are potentially able to reverse neurological sequelae but still require well designed clinical trials studies to prove their efficacy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-M.C., C.A.P. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L., M.S., S.A.A. and L.P.; writing—review and editing, A.L., M.S., S.A.A., L.P., K.W., G.L.B., C.A.P., A.C. and S.-M.C.; visualization, A.L., M.S. and S.A.A.; supervision, S.-M.C.; project administration, S.-M.C. and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T. Attributes and predictors of long COVID [published correction appears in Nat Med]. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groff, D.; Sun, A.; Ssentongo, A.E. Short-term and Long-term Rates of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2128568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkodaymi, M.S.; Omrani, O.A.; Fawzy, N.A. Prevalence of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premraj, L.; Kannapadi, N.V.; Briggs, J. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 434, 120162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, M.I.; Palaiodimou, L.; Bakola, E. Neurological manifestations of long-COVID syndrome: A narrative review. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2022, 13, 20406223221076890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nersesjan, V.; Amiri, M.; Lebech, A.M. Central and peripheral nervous system complications of COVID-19: A prospective tertiary center cohort with 3-month follow-up. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 3086–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghi, E.; Giussani, G.; Westenberg, E. Acute and post-acute neurological manifestations of COVID-19: Present findings, critical appraisal, and future directions. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 2265–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estiri, H.; Strasser, Z.H.; Brat, G.A. Evolving Phenotypes of non-hospitalized Patients that Indicate Long COVID. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Dercon, Q.; Luciano, S.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Harrison, P.J. Incidence, co-occurrence, and evolution of long-COVID features: A 6-month retrospective cohort study of 273,618 survivors of COVID-19. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.L.; Clark, J.R.; Orban, Z.S.; Lim, P.H.; Szymanski, A.L.; Taylor, C.; DiBiase, R.M.; Jia, D.T.; Balabanov, R.; Ho, S.U.; et al. Persistent neurologic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in non-hospitalized COVID-19 “long haulers”. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2021, 8, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Tomasoni, D.; Falcinella, C. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 611.e9–611.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.; Mehta, H.; Sharma, S. Risk Factors Associated with Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 in an EHR Cohort: A National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Analysis as Part of the NIH RECOVER Program. medRxiv 2022. medRxiv:2022.08.15.22278603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffolani, S.; Iencinella, V.; Cimatti, M.; Tavio, M. Long COVID-19 syndrome as a fourth phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Infez. Med. 2022, 30, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.M.; Liu, T.C.; Motwani, Y. Factors Associated with Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC) After Diagnosis of Symptomatic COVID-19 in the Inpatient and Outpatient Setting in a Diverse Cohort. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1988–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parotto, M.; Myatra, S.N.; Munblit, D.; Elhazmi, A.; Ranzani, O.T.; Herridge, M.S. Recovery after prolonged ICU treatment in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 812–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.L.; Koralnik, I.J.; Liotta, E.M. Therapeutic Approaches to the Neurologic Manifestations of COVID-19. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 1435–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosifescu, A.L.; Hoogenboom, W.S.; Buczek, A.J.; Fleysher, R.; Duong, T.Q. New-onset and persistent neurological and psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 compared to influenza: A retrospective cohort study in a large New York City healthcare network. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 31, e1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Yuan, D.; Chen, D.G. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell 2022, 185, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, P.E.; Kirwan, J.P.; Rosen, C.J. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: A metabolic perspective. Elife 2022, 11, e78200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; Deeks, S.G. Early clues regarding the pathogenesis of long-COVID. Trends Immunol. 2022, 43, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, H.; Fokaidis, V. Identifying Contextual and Spatial Risk Factors for Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: An EHR-Based Cohort Study from the RECOVER Program. medRxiv 2022. medRxiv:2022.10.13.22281010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainous, A.G., III; Rooks, B.J.; Wu, V.; Orlando, F.A. COVID-19 Post-acute Sequelae Among Adults: 12 Month Mortality Risk. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Torres, B.; Delanerolle, G.; Okusi, C. Differences in Clinical Presentation with Long COVID after Community and Hospital Infection and Associations with All-Cause Mortality: English Sentinel Network Database Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e37668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Liu, J.; Liu, M. Effect of COVID-19 Vaccines on Reducing the Risk of Long COVID in the Real World: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, W.D.; Sherwood, O.; Banerjee, A.; Togt, V.; Hishmeh, L.; Rossman, J. The Impact of COVID Vaccination on Symptoms of Long COVID: An International Survey of People with Lived Experience of Long COVID. Vaccines 2022, 10, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, B.; Sorboni, S.G.; Javanmard, A.R.; Mottaghi, S.S.; Mehrabi, M.R.; Sorouri, F.; Abbasi, A.; Jahanafrooz, Z. Variants in ACE2; potential influences on virus infection and COVID-19 severity. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2021, 90, 104773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlendick, B.; Schönfelder, K.; Breuckmann, K.; Elsner, C.; Babel, N.; Balfanz, P.; Dahl, E.; Dreher, M.; Fistera, D.; Herbstreit, F.; et al. ACE2 polymorphism and susceptibility for SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity of COVID-19. Pharm. Genom. 2021, 31, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglietta, G.; Diodati, F.; Puntoni, M.; Lazzarelli, S.; Marcomini, B.; Patrizi, L.; Caminiti, C. Prognostic Factors for Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Díaz-Gil, G.; Gómez-Esquer, F.; Gil-Crujera, A.; Gómez-Sánchez, S.M.; Ambite-Quesada, S.; Palomar-Gallego, M.A.; Pellicer-Valero, O.J.; Giordano, R. Genetic Association between ACE2 (rs2285666 and rs2074192) and TMPRSS2 (rs12329760 and rs2070788) Polymorphisms with Post-COVID Symptoms in Previously Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors. Genes 2022, 13, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, T.M.; Buchmeier, M.J. Coronavirus spike proteins in viral entry and pathogenesis. Virology 2001, 279, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heurich, A.; Hofmann-Winkler, H.; Gierer, S.; Liepold, T.; Jahn, O.; Pöhlmann, S. TMPRSS2 and ADAM17 cleave ACE2 differentially and only proteolysis by TMPRSS2 augments entry driven by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Vasilieva, N. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003, 426, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Song, E.; Zhang, C.; Israelow, B. Neuroinvasion of SARS-CoV-2 in human and mouse brain. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20202135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, J.; Radke, J.; Dittmayer, C. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brann, D.H.; Tsukahara, T.; Weinreb, C. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandemirli, S.G.; Altundag, A.; Yildirim, D.; Tekcan Sanli, D.E.; Saatci, O. Olfactory Bulb MRI and Paranasal Sinus CT Findings in Persistent COVID-19 Anosmia. Acad. Radiol. 2021, 28, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butowt, R.; Meunier, N.; Bryche, B.; Bartheld, C.S. The olfactory nerve is not a likely route to brain infection in COVID-19: A critical review of data from humans and animal models. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, L.; Albecka, A.; Mallery, D.L. SARS-CoV-2 Infects the Brain Choroid Plexus and Disrupts the Blood-CSF Barrier in Human Brain Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhl, L.; He, L.; Sun, Y. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is expressed in mouse pericytes but not endothelial cells: Implications for COVID-19 vascular research. Stem Cell Rep. 2022, 17, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A.; Frontera, J.; Placantonakis, D.G.; Galetta, S.; Balcer, L.; Melmed, K.R. Cerebrospinal fluid from COVID-19 patients with olfactory/gustatory dysfunction: A review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2021, 207, 106760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Bartley, C.M.; Chow, R.D. Divergent and self-reactive immune responses in the CNS of COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschke, J.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Hagel, C. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: A post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.T.; Miller, E.H.; Glendinning, M.D. COVID-19 neuropathology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York Presbyterian Hospital. Brain 2021, 144, 2696–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.C.; Kern, F.; Losada, P.M. Dysregulation of brain and choroid plexus cell types in severe COVID-19 [published correction appears in Nature. Nature 2021, 595, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Zhou, J.; He, Q. SARS-CoV-2 infection in the mouse olfactory system. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivgoulis, G.; Fragkou, P.C.; Lachanis, S. Olfactory bulb and mucosa abnormalities in persistent COVID-19-induced anosmia: A magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, e6–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Nakano, Y. Examination and classification of human olfactory mucosa in patients with clinical olfactory disturbances. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 1988, 245, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaira, L.A.; Hopkins, C.; Sandison, A. Olfactory epithelium histopathological findings in long-term coronavirus disease 2019 related anosmia. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2020, 134, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, G.D.; Lazarini, F.; Levallois, S.; Hautefort, C.; Michel, V.; Larrous, F.; Verillaud, B.; Aparicio, C.; Wagner, S.; Gheusi, G.; et al. COVID-19-related anosmia is associated with viral persistence and inflammation in human olfactory epithelium and brain infection in hamsters. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabf8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, C.; Tang, L. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 434–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xiao, J.; Sun, R. Prolonged Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in Body Fluids. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1834–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.C.Y. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients with COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, E.M.M. Microbiota-Brain-Gut Axis and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2017, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataf, S.; Pays, L. Molecular Insights into SARS-CoV2-Induced Alterations of the Gut/Brain Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daulagala, S.W.P.L.; Noordeen, F. Epidemiology and factors influencing varicella infections in tropical countries including Sri Lanka. Virusdisease 2018, 29, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smatti, M.K.; Al-Sadeq, D.W.; Ali, N.H.; Pintus, G.; Abou-Saleh, H.; Nasrallah, G.K. Epstein-Barr Virus Epidemiology, Serology, and Genetic Variability of LMP-1 Oncogene Among Healthy Population: An Update. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meng, M.; Zhang, S.; Dong, X.; Sun, W.; Deng, Y.; Li, W.; Li, R.; Annane, D.; Wu, Z.; Chen, D. COVID-19 associated EBV reactivation and effects of ganciclovir treatment. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2022, 10, e597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, J.E.; Okyay, R.A.; Licht, W.E.; Hurley, D.J. Investigation of Long COVID Prevalence and Its Relationship to Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation. Pathogens 2021, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Pablos, M.; Paiva, B.; Montero-Mateo, R.; Garcia, N.; Zabaleta, A. Epstein-Barr Virus and the Origin of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 656797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monje, M.; Iwasaki, A. The neurobiology of long COVID. Neuron 2022, 110, 3484–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Wood, J.; Jaycox, J.; Lu, P.; Dhodapkar, R.M.; Gehlhausen, J.R.; Tabachnikova, A.; Tabacof, L.; Malik, A.A.; Kamath, K.; et al. Distinguishing features of Long COVID identified through immune profiling. medRxiv 2022. medRxiv:2022.08.09.22278592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Reviejo, R.; Tejada, S.; Adebanjo, G.A.R.; Chello, C.; Machado, M.C.; Parisella, F.R.; Campins, M.; Tammaro, A.; Rello, J. Varicella-Zoster virus reactivation following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination or infection: New insights. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 104, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Chen, C.; Tang, J. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and Paxlovid) for COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawood, A.A. The efficacy of Paxlovid against COVID-19 is the result of the tight molecular docking between Mpro and antiviral drugs (nirmatrelvir and ritonavir) [published online ahead of print, 2 November 2022]. Adv. Med. Sci. 2022, 68, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Nirmatrelvir and the Risk of Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS). medRixv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.V.; Jain, S.; Parveen, S. The outcome of fluticasone nasal spray on anosmia and triamcinolone oral paste in dysgeusia in COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.A.; Mohamady, A.A.; Elsayed, R.A.; Elawady, M.A.; Ghallab, A.F. Corticosteroid nasal spray for recovery of smell sensation in COVID-19 patients: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kelly, B.; Vidal, L.; McHugh, T.; Woo, J.; Avramovic, G.; Lambert, J.S. Safety and efficacy of low dose naltrexone in a long covid cohort; an interventional pre-post study. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2022, 24, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, S.A.; Badawi, A.M.; Mansour, H.F. Insulin fast-dissolving film for intranasal delivery via olfactory region, a promising approach for the treatment of anosmia in COVID-19 patients: Design, in-vitro characterization and clinical evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaeian, A. Effect of Intranasal Insulin on Olfactory Recovery in Patients with Hyposmia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 158, 1134–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]